Tuna Haimation Garum

GARUM LUSITANO by CAN THE CAN

Garum sauce produced with Atlantic bluefin tuna, fished in the waters of the Atlantic. High quality garos called Haimation, obtained from the first filtered liquid of the process of maceration of tunny entrails with gills fluid and blood.

Made with Sado salt. Fresh Koji added, ferment in Sado rice.

Produced in small batches, for a unique blend of bold flavor & soft scent. Enjoy.

Depending on the batch, there may be differences in tone and transparency

Ingredients: tuna, koji and salt

TUNA HAIMATION

CONT. NET 50ML

WILD CAUGHT FISH

CONTAINS NO COLOURING NOR CONSERVATIVE

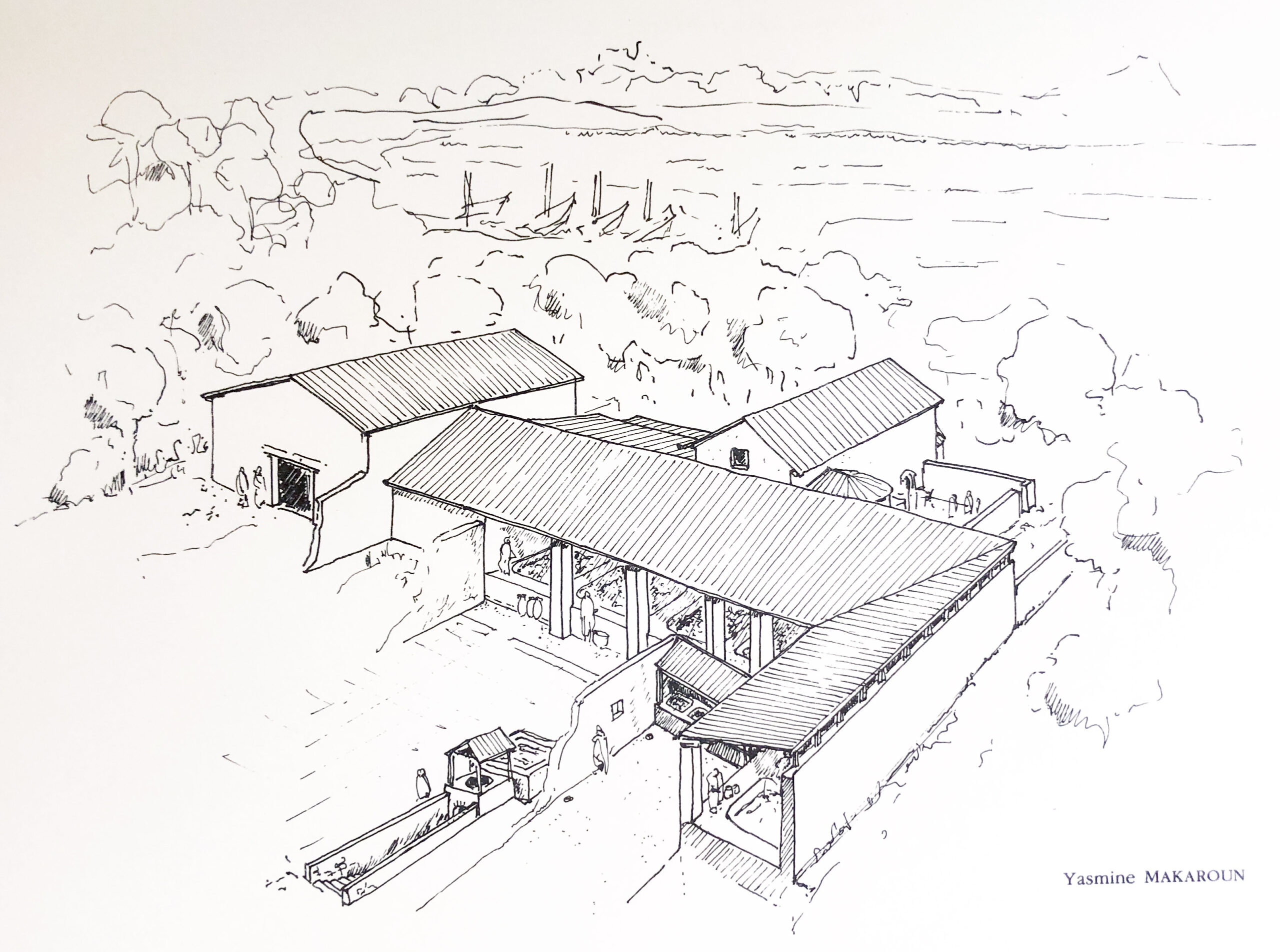

Garum was without a doubt the favorite condiment of the Romans. Made from various fermented fish parts, it was a type of fish sauce produced throughout the empire.

Highly protein, GARUM, increases the intensity of the flavor.