Trinh Fred Carpenter, Metro State and Gaius Stern, UC Berk (retired

fred.carpenter@metrostate.edu

gaius@berkeley.edu

The poet Ovid was exiled to the far reaches of the ancient Roman Empire by the Emperor Augustus in 8 CE. In his exile at Tomis, now modern day Romania, he lamented the things he missed, including food and the sound of his language. It is with this thought that we discuss a common ingredient in Roman cookery, garum, which has suffered unfair notoriety as “a disgusting sauce made from rotting fish guts”[1] by those who have never tasted it. The journey of garum from prominence to exile and return strangely runs parallel to Ovid whose fame returns centuries after his exile.

[1]See for example, clumsydisaster: “… the mere idea of fish guts fermenting in a jar just makes me want to gag. It was popular enough though that its end product was sought after by pretty much everyone. It would be mixed with wine, vinegar, black pepper, oil, diluted with water, etc. They even thought it was the best cure for dysentery and was a great hair remover. It seems that not only are the Romans out for tastiness but they’re out for versatility.

I’d like to add though that the end product (after all the petrifying and liquifying and obvious vomiting I’d have been doing if I had to make it) was considered quite yummy. Kind of on par to certain Asian sauces used in Asian cuisine today. I think I just get caught on the smell. Could you imagine that? Yuck.” From https://clumsydisaster.wordpress.com/2011/08/25/what-is-that-smell/ posted 25 Aug. 2011, 20 Sept. 2012.

What is garum? Garum, to put it simply, is a preserved fish product. Its origins trace to ancient Greece with the word, garos, and into Latin as garum. Garum is simply salt, fish, sun and time: Time for the fish to decay into a liquid and decomposed flesh at the bottom of a container. Garum is produced in a very similar manner to Asian fish sauce, or perhaps more correctly, Asian fish sauce is produced much like Garum. We can assume that the nutritional profile is similar with a product that is rich in umami or the fifth taste, usually associated with savoriness. It has a taste that is called “meaty.” Foods that are considered heavy umami are rich in glutamic acid, ribonucleotides, and inosinates, such as soy sauce, tomatoes, mushrooms, cheese, and preserved meats. Fish sauce is also rich in nutrients and can serve as a source of amino acids and protein (Thongthai). Brillat Savarin said that, “cheese was milk’s leap towards immortality,” and the same could be said of garum. Using salt and fermentation, a volatile product, fish, is transformed into a long stored food item that is easily transported over long distance and served as a source of salt and protein to a growing empire that was still eaten into the Byzantine period.

The earliest surviving mention of a form of garum comes from the Greeks from the 5th century BCE Athenian Old Comedy playwright Cratinus (519 – 422 BC), an older contemporary of Sophocles.[2]

[2]Kock fragment 1.95 apud Athen. 2.67c: ΓΑΡΟΣ. Κρατῖνος 1.95 K: ὁ τάλαρος ὑμῶν διάπλεως ἔσται γάρου.

Regarding garum: Cratinus says — Your basket will be full of pickled fish sauce.

For other sources mentioned throughout viz. Manil. Astron. 5.671 ff; Seneca Ep. 95. 25; Pliny NH 31.93ff; Martial Epig. 3.77.5, 11.27; Oneirocritica1.68; Isidore of Seville, Etymologies, 20.3.19-20.

Other fragments survive from Pherecrates, Sophocles, Aeschylus and a poet named Plato.[3]

Our main source of information on how to use garum and Roman cookery is the lone surviving cookbook from the Roman empire, Apicius’ De re coquinaria (“On the Subject of Cooking:) Over 70% of the ~465 recipes in the cookbook use liquamen, the first draw of garum (think of virgin olive oil). We are at a loss for the absence of these and other sources except as quotes in the Deipnosophistae of Athenaeus, a collection of dinner table discussions on everything from human virtues to types of vases and cups. Garum comes up as a subject at least twice, Deip. 2.67c, 9.366c: “And I also see garum sauce beaten up in a mixture with vinegar.

[3]Kock fragments 1,197, 545 = T.G.P.2 264, Kock fragment 1.656, 55 = T.G.P.2 71 apud Athen. 2.67c: Φερεκράτης 1.197 K: ἀνεμολύνθη τὴνὑπήνην τῷ γάρῳ.

And Pherecrates says—

His beard was all soaked with fish sauce.

Σοφοκλῆς Τριπτολέμῳ fr. 545 N: τοῦ ταριχηροῦ γάρου.

And Sophocles, in his Triptolemus, says — Eating this briny season’d pickle.

Πλάτων 1.656 K: ἐν σαπρῷ γάρῳ βάπτοντες ἀποπνίξουσί με. = fr. 198 Edmonds.

ὅτι δ᾽ ἀρσενικόν ἐστι τοὔνομα Αἰσχύλος δηλοῖ εἰπών fr. 55 N: καὶ τὸν ἰχθύων γάρον.

And Plato the comic writer says—

These men will choke me, steeping me in putrid pickle.

But the word γάρος, fish sauce, is a masculine noun, as Aeschylus proves, when he says “and the fishy sauce.”

“And I also see garum sauce beaten up in a mixture with vinegar. I know that in our day some inhabitants of Pontus prepare a special kind which is called vinegar garum.”[4] This line indicates yet another far from Rome local industry of garum production in the 2nd century AD, for the consumption of garum became an identity establishing feature of the Roman Empire, not unlike making a daily visit to the public baths or wearing the toga.

The Romans had four types of preserved fish product that we will broadly call garum:

· Garum: The general product made from preserving fish with salt. Later becomes interchangeable in word use with liquamen. Earlier sources indicate that this particular classification was made from blood and innards of larger fish, such as tuna and mackerel.

· Liquamen: First liquid draw from garum without fish flesh

· Muria: By product of fish salting process. The liquid brine

· Allex: Undissolved fish parts

Garum had both its fans and detractors, surprisingly, often the same people, including Seneca and Pliny, being but two of many. The astronomer Manlius Astron. 5.671 describes its preparation:

This part is better if the juices are given up; that part when juices are retained,

On this side a precious bloody matter (sanies) flows and vomits out the flower of the gore

And vomits out the taste after salt is mixed in, it tempts the lips;

on that side the putrid slaughter of the crowd (of fish) flow all together

and mix their shapes in another melting semi-liquid slosh

and provide a widely used liquid for foods.

…

their mutual gift of liquid flows out alike

and their inner parts melt and issue forth as a stream of decomposition.

Nay in fact they could fill the great salt pans

and cook the sea and also extract the poison of the salt sea.[5]

[4]Athen. Deip. 9.366c: ὁρῶ δὲ καὶ μετὰ ὄξους ἀναμεμιγμένον γάρον. οἶδα δὲ ὅτι νῦν τινες τῶν Ποντικῶν ἰδίᾳ καθ᾽ αὑτὸ κατασκευάζονταιὀξύγαρον. The translation came from Bill Thayer’s scan of the Loeb.

[5]Manil. Astron. 5.671-75: hinc sanies pretiosa fluit floremque cruoris / evomit ex mixto gustum sale temperat oris; illa putris turbae strages confunditur omnis / permiscetque suas alterna in damna figuras / communemque cibis usum sucumque ministrat. Check also Geoponika 20.46.6.

Seneca the Younger Ep. 95. 25 advises his correspondent Lucilius Junior against gluttony and excess when he says “What? Don’t you think the garum made by our allies, the bloody remains of harmful (the meaning may be poisonous) fish, burns the stomach (diaphragm) with salted putrification.[6]

Garum was a luxury good, produced in many parts of Italy, so if Seneca and Lucilius Junior know others import the Spanish product, not only is it more expensive (wastefulness) but actually harmful due to the local Spanish fish from which it is produced. It had the allure of pufferfish sushi or questionable Russian caviar. In an age of vice, described to a considerable extent in Petronius, people were engaging in a doubly harmful form of conspicuous consumption, as Eugene Weber of UCLA liked to mention, just to show they could afford to get the garum sociorum, even though it was not better than that of Pompeii. Some distantly-made garum was a status symbol (like Belgian beer or champagne today).

Pliny the Elder NH 31.43-44.93-97 describes both the spread of garum and the widespread garum production industry. He says garum has a delicious flavor and medicinal benefits, making it a luxury good and at the same time an edible form of Roman-ness.

There is yet another kind of choice liquor, called garum, consisting of the guts of fish and the other parts that would otherwise be considered refuse; these are soaked in salt, so that garum is really the bloody matter of the putrefying leftovers [illa putrescentium sanies]. Once this used to be made from a fish that the Greeks called garos; they showed that by fumigation with its burning head the after-birth was brought away. Today the most popular garum is made from the scomber in the fisheries of Carthago Spartaria—it is called garum of the allies—1,000 sesterces being exchanged for about two congii of the fish. … Clazomenae, too, is famous for garum, and so are Pompeii and Leptis, just as Antipolis and Thurii are for muria, and today too also Delmatia.

44.95. Allex is sediment of garum, the dregs, neither whole nor strained. It has, however, also begun to be made separately from a tiny fish, otherwise of no use. The Romans call it apua, the Greeks aphye, because this tiny fish is bred out of rain. The people of Forum Julii call lupus (wolf) the fish from which they make garum. Then allex became a luxury, and its various kinds have come to be innumerable; garum for instance has been blended to the color of old honey wine, and to a taste so pleasant that it can be drunk. But another kind <of garum> is devoted to superstitious sex-abstinence and Jewish rites, and is made from fish without scales. Thus allex has come to be made from oysters, sea urchins, sea anemones, and mullet’s liver, and salt to be corrupted in numberless ways so as to suit all palates. These incidental remarks must suffice for the luxurious tastes of civilized man. Allex however itself is of some use in healing. For allex both cures itch in sheep, being poured into an incision in the skin, and is a good antidote for the bites of dog or sea draco; it is applied on pieces of lint. By garum too are fresh burns healed, if it is poured over them without mentioning garum. Against dog-bites it is beneficial and especially against those of crocodiles..(7)

[6]Quid? Illud sociorum garum, pretiosam malorum piscium saniem, non credis urere salsa tabe praecordia? For garum sociorum, see Robert Etienne, “A propos du ‘garum sociorum’,” Latomus 29 (1970) 297-313. Translation Gaius Stern, tabes = corruption, wasting away.

[7]Aliud etiamnum liquoris exquisiti genus, quod garum vocavere, intestinis piscium ceterisque quae abicienda essent sale maceratis, ut sit illa putrescentium sanies. hoc olim conficiebatur ex pisce quem Graeci garon vocabant, capite eius usto suffito 94extrahi secundas monstrantes. nunc e scombro pisce laudatissimum in Carthaginis Spartariae cetariis—sociorum id appellatur—singulis milibus nummum permutantibus congios fere binos. … laudantur et Clazomenae garo Pompeique et Leptis, sicut muria Antipolis ac Thuri, iam vero et Delmatia.

All the same, while reporting garum’s merits and medicinal value, Pliny disgusts the modern reader by mentioning the decomposing fish. This seemingly very mixed presentation probably did not faze the Roman audience who was practical and not disgusted by the same smells and tastes as us (e.g. sulphur as a cleanser, fullers using urine as detergent). In the ancient world, nothing edible was thrown away, because many people struggled with hunger.

The poet Martial 3.77.5, like Seneca before him, regards garum as a luxury good, but one that everyone can afford, and that everyone enjoys. He criticizes a certain Baeticus for eating capers and onions “swimming” in putrid allex: capparin et putri cepas allece natantis. Again here the idea is that Baeticus is no gourmet. He shuns hare, boar, thrush, and mullet (the latter much praised by T. Annius Milo in a letter to Cicero), but eats simple capers and onions and pours on the garum. Baeticus is the sort of person who prefers burgers at MacDonalds over duck confit at a French restaurant, and any kind of mustard will do. He does not need Grey Poupon.

Likewise, in a second epigram, Martial 11.27, the unnamed girlfriend of Martial’s friend Flaccus is satisfied with fairly modest requests from her boyfriend, including garum,whereas Martial’s own girlfriend makes far greater demands, which he fails to deliver, but he likes the fact that she has highbrow tastes. For us, the point emerges from both epigrams that garum is something everyone can afford, at least the less expensive varieties, so as a luxury good it compares to exotic jam in the US: not everyone can afford to buy imported Swedish cloudberry jam or Michigan Thimbleberry jam at $12 per eight-ounce bottle, but everyone can afford Safeway raspberry jam (9)

You are made of iron, Flaccus, if your cock can stand

when your girlfriend begs you for six cyathi (half a pint) of garum,

or asks in vain for two pieces of tuna or a slim fillet of mackerel

and thinks herself unworthy of a whole bunch of grapes;

one to whom her maid with delight carries on a red platter

allecem fish-sauce, but she devours it immediately.[8]

44.95 Vitium huius est allex atque imperfecta nec colata faex. coepit tamen et privatim ex inutili pisciculo minimoque confici. apuam nostri, aphyen Graeci vocant, quoniam is pisciculus e pluvia nascitur. Foroiulienses piscem ex quo faciunt lupum appellant. transiit deinde in luxuriam, creveruntque genera ad infinitum, sicuti garum ad colorem mulsi veteris adeoque suavitatem dilutum ut bibi possit. aliud vero . . . castimoniarum superstitioni etiam sacrisque Iudaeis dicatum, quod fit e piscibus squama carentibus. sic allex pervenit ad ostreas, echinos, urticas maris, mullorum iocinera, innumerisque generibus ad saporis gulae coepit sal tabescere. 96 haec obiter indicata sint desideriis vitae, et ipsa tamen non nullius usus in medendo. namque et allece scabies pecoris sanatur infusa per cutem incisam, et contra canis morsus draconisve marini prodest, in linteolis autem concerptis inponitur. 97 Et garo ambusta recentia sanantur, si quis infundat ac non nominet garum. contra canum quoque morsus prodest maximeque crocodile …

[8]Ferreus es, sista repotest tibi mentula, Flacce,/ cum te sexcyathos oratamica gari. vel duo frusta rogat cybii tenuemve lacertum nec dignam toto se botryone putat; cui portat gaudens ancilla paropside rubra allecem, sed quam protinus illa voret.

The professional diviner from 2nd century AD Ephesus, Artemidorus Daldianus Oneirocritica 1.68, was no fan of garum: idcirco Artemidorus garum nihil aliud esse nisi putredinem contendit: ouden allo h shpedwn, quae sentential in Zonorae et Suidae lexica abiit; – “about it, Artemidorus contends that garum is nothing other than putrid when he says (in Greek) ‘nothing other than rottenness,’ which opinion was absent in the lexicons of Zonoras and Suidas.” (10)

Garum was used extensively in Roman cuisine and found throughout the Empire. Garum factories were found in Pompeii and Roman Hispania. Further evidence of garum’s availability and common access appear in two price sources, Tariff of Zarai, CE 202, and the Price Edict of Diocletian, AD 301. In the Tariff of Zarai the pricing of garum is comparable to wine of the same amount. In the Price Edict of Diocletian the fish sauce was broken into two quality classifications (first and second). Again, in comparing with other goods listed in the Edict, it is found that first and second quality garum was priced comparably with first and second class honey. Inferring from these two sources we can deduce that garum was common enough to be taxed regularly and fell within the price access of the Roman public, corroborating our inferences from Martial (above) 150 years later. Further, excavation in Pompeii and Herculaneum show amphorae of garum in the homes across a wide stratum of society with all four types found.

Obviously garum started in Italy for local consumption, but as the Roman Empire expanded, so did the need for garum and the need for local production. And the need grew as it went, meaning that many new Romans adopted a taste for garum, either because it tastes good (as we argue) or because its consumption was seen as a status symbol. Augustus settled many Italians in the provinces in the settlements of the 20s BC. One mostly overlooked way they Romanized the provinces, besides recreating grid-pattern Roman cities with baths and a forum, was to bring their tongues with them, meaning both the speaking of Latin – on which much has been said and written before – but also the taste for Roman food. They imported and eventually produced their own garum to enjoy the flavors of home far from Italy.

[9]I can hardly recommend highly enough Thimbleberry Jam to those who can afford it, sold in eight ounze jars for $12 each, http://thimbleberryjamlady.com/store/index.php?main_page=index&cPath=1&zenid=up3j3qmnejg0ms7u34dbu530q1

[10]See also Galen, Concerning the Properties of Foods 1.1.42-43, Corpus medicorum graecorum, 5.4.2.

Because of the species of fish used, production of garum was mostly based around the shores of the Mediterranean, and the products of Hispania, Lusitania, and North Africa near Carthage were considered the best.[11] Remains of the garum works in present day Spain testify to the size of production and the wide shipping network of the product. Garum production eventually spanned coastal Hispania, Lusitania, Gaul, and North Africa. The Eastern Empire also had processing centers along the Black Sea even beyond Roman territory in the Crimea and the Strait of Kertch. The most extensive findings have been in Spain and Portugal; one location, Troia had the production capacity of 600 cubic metres. The largest center is at Lixus in Nothern Morocco, whose capacity was greater than 1000 cubic metres. These sites indicate how large the production was of the garum. It was so widely consumed that a kosher variety was available for the Jewish population in Alexandria.

It is a wonder then that garum declined completely in its use and distribution in the Roman and Byzantine world. But we know what disrupted the centuries-long production and trade of garum: war and the loss of order. Beyond the basics of fish, salt and time in producing garum in the Byzantine period large fishing fleets were essential and so were beachfront facilities (especially after regulations were put in place by Constantine Harmenopoulus that garum works could not be within a certain distance of a town due to the odors) and safe shipping routes from areas of production to faraway clients. Other factors that may have affected garum pricing and access were the requirement of a large workforce, land for facilities, and credit during a tumultuous time where shipping routes would not necessarily be secure. The Empire’s decline and the contraction of the Empire pulled apart the trade routes and threads from production to the client. According to archaeologist Claudio Giardino, two additional issues were the salt tax, a heavy burden on a major ingredient of garum, and the lack of security in coastal regions once the Empire could no longer protect itself. The increase in production and shipping costs made garum far more difficult product to acquire. For a fuller sense of the change in Roman cuisine through time, observe the list of ingredients and flavoring ingredients that could no longer or rarely be found, including sylphium, lovage, passum, and defrutum. However, the love of preserved fish is still found in modern Italy with salted cod taking the place of Egyptian red mullet, salted anchovy for garum/muria/alec, and salted tuna. Interestingly enough, garum was rediscovered by Cistercian monks in Campania where Colatura di Alici is produced. It is produced differently than classic garum and Asian fish sauce, where the brine of the salted anchovies is drawn away from the vat as fermentation occurs. It is closer to muria than classic liquamen, which was decanted from the container.

[11]Strab. Geog. 3.4.6: εἶθ᾽ ἡ τοῦ Ἡρακλέους νῆσος ἤδη πρὸς Καρχηδόνι, ἣν καλοῦσι Σκομβραρίαν ἀπὸ τῶν ἁλισκομένων σκόμβρων, ἐξ ὧν τὸἄριστον σκευάζεται γάρον: εἴκοσι δὲ διέχει σταδίους καὶ τέτταρας τῆς Καρχηδόνος.

Next is the island of Hercules, near to Carthage, and called Scombraria, on account of the mackerel taken there, from which the finest garum is made. It lies 24 stadia from Carthage

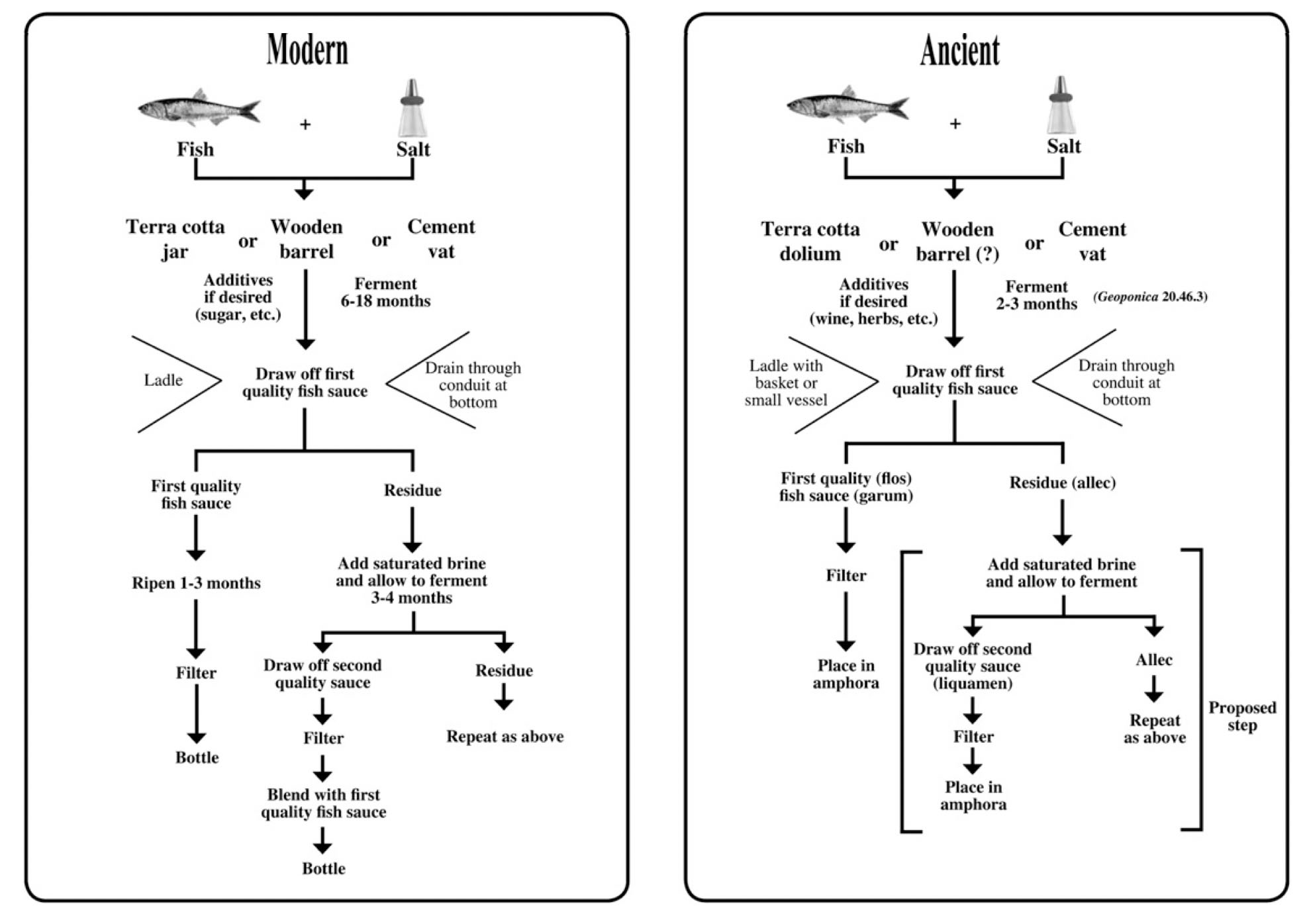

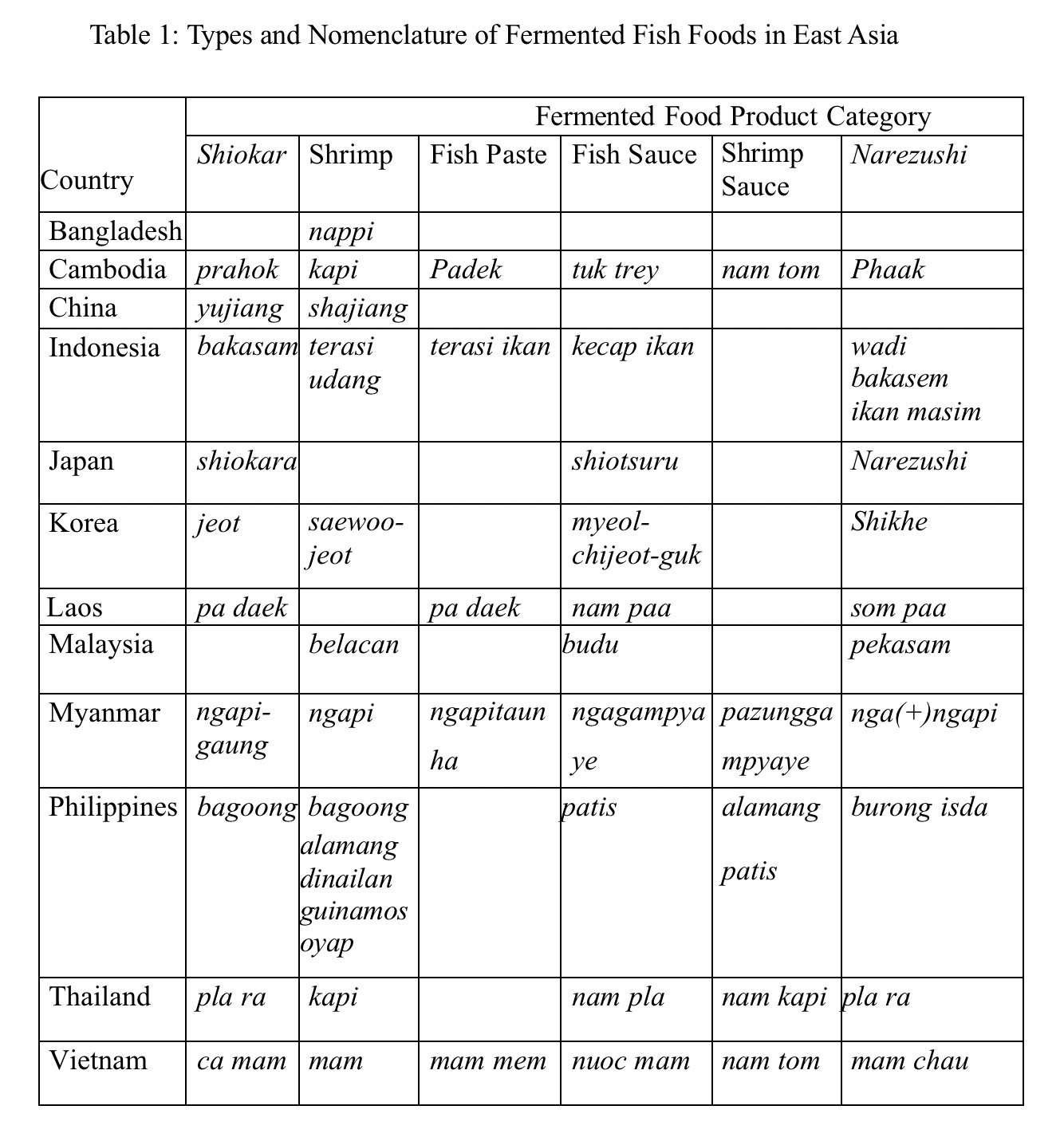

In contrast, the production of fish sauce in Asia has been uninterrupted for centuries. There is a question of west-east transfer of fish sauce technology, but this paper avoids that controversy and limits its focus to the similarity of the two food products developed in different areas of the world. One does not know for certain whether Asian fish sauce (fish water) originated in China or Southeast Asia. Apparently, the diffusion of the concept emerges out of China prior to the Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220). Roman and Vietnamese fish sauce have a similar ratio of fish to salt ≤ 5:1, but the Romans fermented garum for less time before bottling it. Both Roman and Southeast Asian cuisines use fish sauce in similar manners, as both an ingredient in cooking and as a condiment that can be diluted with other ingredients like vinegar or sweetener. Both have grades of quality. Vietnamese and Thai fish sauce divide into four grades. The first grade is similar to Roman flos, it is the first draw from the vat. The fish remains from the vat are mixed with salt water to ferment for two to three additional months to create the second and third grades. The is where the fish remains from the third grade fermentation are boiled with salt water to produce the lowest grade (probably what Baeticus slathers on his capers. For a clearer chart of production, see Curtis’ chart from “Umamni and the Food of Classical Antiquity. (12)

Asian fish sauce production is as diffuse as the ancient Roman was, but rather than suffer a fall back in production, it has expanded into a multi-million dollar industry with EU origin classification. The popularity of Southeast Asian cuisines, in particular, Thai and Vietnamese has magnified the customer base of fish sauces (13)

[12]Robert I. Curtis, “Umamni and the Food of Classical Antiquity,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 90.3 (2009), 7125-85.

[13]Another area of expansion is Africa, where fish sauce is used in Senegalese and other West African cuisines sometimes to replace other preserved fish products (momone or guedj). Though fish sauce is on the rise, there are still issues that could see the decline of Asian fish sauces, such as climate change and the collapse of fish stocks in the coastal regions of Asia. Vietnamese fish sauce uses pelagic fish, such as anchovy. The Romans used more varieties of fish including larger fish, such as tuna and mackerel in addition to pelagic fish. The Asian industry uses a smaller base of fish species in its production.

In the end, we have a food item that has been around to see its own decline and re-birth. Fish sauce was a dominant flavoring agent of the large Roman Empire and declined with it. It simultaneously emerged in Asia and now is the dominant flavoring agent for cuisines that are finding homes throughout the global economy. Ovid, I think, would have been pleased to eat at a Thai or Vietnamese restaurant, if one opened in Tomi.

Now try a bit of Roman patina cooked with garum and pine nuts

References:

Brothwell, Don R, and Patricia Brothwell. Food in antiquity: a survey of the diet of early peoples. JHU Press, 1969.

Corcoran, Thomas H. “Roman fish Sauces,” Classical Journal 58 (1963), 204-10;

and Curtis, Robert I. “In Defense of Garum,” Classical Journal 78 (1983), 232-40.

Curtis, Robert Irvin. “Umamni and the Food of Classical Antiquity,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 90.3 (2009), 7125-85.

Garum and Salsamenta: Production and Commerce in Materia Medica. Brill Academic Pub. (1991).

The Production and Commerce of Fish Sauce in the Western Roman Empire: A social and Economic Study. (Diss. 1978).

Ancient food technology. Brill Academic Pub. (2001).

Dalby, Andrew, and Sally Grainger. The classical cookbook. Getty Publications, 1996.

Faas, Patrick, and Shaun Whiteside. Around the Roman table. University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Giacosa, Ilaria Gozzini. A taste of Ancient Rome. Rand Corporation, 1994.

Grainger, Sally. Cooking Apicius: Roman recipes for today. Prospect Books, 2006.

Grimal, Pierre and Monod, Thomas “Sur le veritable nature du ‘garum,'” Rev. Étud. ancien., 34: 27-38, 1952;

Claude Jardin, “Garum et sauces de poisson de 1’inriquiti,” JZiV. Stud. Liguri, 2T70-96, 1961;

Ruddle, Kenneth, and Naomichi Ishige. “On the origins, diffusion and cultural context of fermented fish products in Southeast Asia.” lobalization, Food and Social Identities in the Asia Pacific Region. Sophia University Institute of Comparative Culture, Tokyo (2010).

Thongthai C, Gildberg A. Asian fish sauce as a source of nutrition. In: Shi J, Ho CT, Shahidi F, eds. Asian functional foods. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis, 2005:215–65.

R. Zahn, “Garum,” A.Pauly, et al, ed. in Real-Encyclopedie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, 80 vols., Stuttgart, J. B. Metzler, 1893-1974, 1st series, 8, cols. 841-849, 1912 (hereinafter referred to as RE).

http://www.thaifoodandtravel.com/features/fishsauce1.html

http://vietworldkitchen.typepad.com/blog/2008/11/fish-sauce-buying-guide.html

Customer Care

CAN THE CAN uses cookies in order to provide you with a better online experience. By continuing your visit to our site you agree to the use of cookies

Contact

reservations@canthecan.net

info@canthecan.net

T. +351 914 007 100

T. +351 218 851 392

Terreiro do Paço 82/83

1100-148 Lisboa – Portugal

Open everyday from 9:00 AM to 1:00 AM